We’re thrilled to report the upcoming announcement of Manuel Márquez-Sterling’s new book, Cuba 1952-1959: The True Story of Castro’s Rise to Power.

The book will be formally announced in a presentation by Prof. Márquez-Sterling at Plymouth State University, where he is teaching a course on that period of Cuban History this semester. The presentation will be held at the the Lamson Library and Learning Commons, 3:00pm on Tuesday November 3, 2009. All in the Plymouth community are welcome to attend.

For information about the the event contact Anne Lebreche at Lamson Library and Learning Commons via e-mail to AMLebreche@plymouth.edu.

We’ve added links to our sidebar to browse or purchase the new book at Amazon.

Wednesday, October 21, 2009

Tuesday, October 20, 2009

1958: Castro General Strike Fails

Cuba History Timeline Events

April 9, 1958

Castro picked the tenth anniversary of the Bogotazo as the day for the strike that would be “the final blow against the dictatorship” of Batista. Castro’s call for his much-vaunted general strike by all Cuban workers was universally ignored, a very visible failure demonstrating Castro and M-26-7 support by Cubans (and particularly Cuban workers) was much smaller than claimed by Castro and reported by his allies. Even his press sympathizers had to acknowledge the total failure of the much heralded “final blow” that would bring down Batista.

US Embassy analysis of strike failure has been gathered and published by de la Cova. The US analysts concluded that the major causes were poor planning and organization by M-26-7 and lack of Castro support by the Cuban people and the trade unions.

Cuba’s labor movement was not merely unsupportive of Castro or his strike call, they were staunch opponents and strong Batista supporters. Union chief Eusebio Mujal (an ex-communist turned strongly anti-communist) was a staunch Batista ally and supporter. Cuba’s trade unions and leadership remained one of the strongest anti-Communist/anti-Castro blocks until the Castro regime purged their leadership and brought them under state control.

Castro’s first attempt at explaining the failure was to claim its failure was a result of threatened deadly force by the “brutal tyrant Batista” against strikers. This explanation was not convincing, since everyone was aware Castro had threatened workers who didn’t strike with death. Moreover, police force could not have prevailed against a clear majority of workers. The next explanation, which endured, was that it was the fault of the Strike Coordinator chosen by Castro himself, Faustino Pérez. Early M-26-7 communiques denounced Pérez as a “traitor” for bungling strike plans, command and control. A contemporaneous Time story is interesting in including both explanations. In the evolving explanations for the failure, a week later Castro also attacked Prio for “living in luxury in Miami" while the rebels fought on bravely, despite severe shortages of military supplies and food.

By the end of the month it was apparent that the failure was a major setback with deep impact for Castro and M-26-7. As Time reported:

There was no doubt that the rebels were hurt, and they showed it. From the chief himself came a summons to his six top provincial lieutenants to head back to the Sierra Maestra, presumably for an agonizing reappraisal. The total failure of Castro's touted "total war" had highlighted 1) his weakness in practical organizing ability, and 2) the movement's lack of a social program to attract Cuba's labor and its Negroes (25% of the total population, some 40% of Oriente's). Said a wealthy, aging Havana rebel last week: "From now on, if Castro wants our money he'll have to take our advice along with it. The days of blind Fidelismo are over."

April 9, 1958

Castro picked the tenth anniversary of the Bogotazo as the day for the strike that would be “the final blow against the dictatorship” of Batista. Castro’s call for his much-vaunted general strike by all Cuban workers was universally ignored, a very visible failure demonstrating Castro and M-26-7 support by Cubans (and particularly Cuban workers) was much smaller than claimed by Castro and reported by his allies. Even his press sympathizers had to acknowledge the total failure of the much heralded “final blow” that would bring down Batista.

US Embassy analysis of strike failure has been gathered and published by de la Cova. The US analysts concluded that the major causes were poor planning and organization by M-26-7 and lack of Castro support by the Cuban people and the trade unions.

Cuba’s labor movement was not merely unsupportive of Castro or his strike call, they were staunch opponents and strong Batista supporters. Union chief Eusebio Mujal (an ex-communist turned strongly anti-communist) was a staunch Batista ally and supporter. Cuba’s trade unions and leadership remained one of the strongest anti-Communist/anti-Castro blocks until the Castro regime purged their leadership and brought them under state control.

Castro’s first attempt at explaining the failure was to claim its failure was a result of threatened deadly force by the “brutal tyrant Batista” against strikers. This explanation was not convincing, since everyone was aware Castro had threatened workers who didn’t strike with death. Moreover, police force could not have prevailed against a clear majority of workers. The next explanation, which endured, was that it was the fault of the Strike Coordinator chosen by Castro himself, Faustino Pérez. Early M-26-7 communiques denounced Pérez as a “traitor” for bungling strike plans, command and control. A contemporaneous Time story is interesting in including both explanations. In the evolving explanations for the failure, a week later Castro also attacked Prio for “living in luxury in Miami" while the rebels fought on bravely, despite severe shortages of military supplies and food.

By the end of the month it was apparent that the failure was a major setback with deep impact for Castro and M-26-7. As Time reported:

There was no doubt that the rebels were hurt, and they showed it. From the chief himself came a summons to his six top provincial lieutenants to head back to the Sierra Maestra, presumably for an agonizing reappraisal. The total failure of Castro's touted "total war" had highlighted 1) his weakness in practical organizing ability, and 2) the movement's lack of a social program to attract Cuba's labor and its Negroes (25% of the total population, some 40% of Oriente's). Said a wealthy, aging Havana rebel last week: "From now on, if Castro wants our money he'll have to take our advice along with it. The days of blind Fidelismo are over."

| |

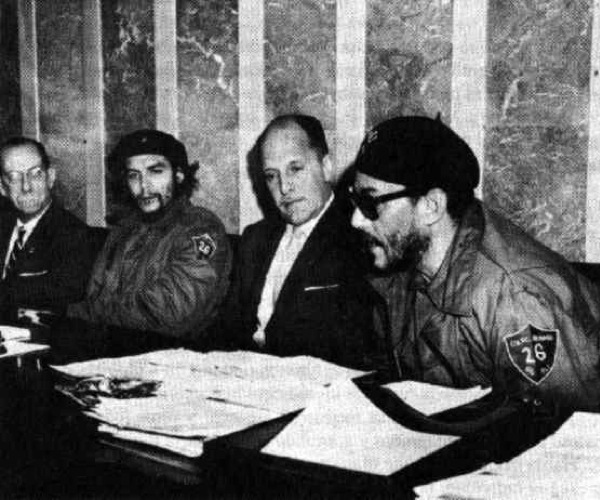

| Faustino Pérez, Havana 1959 (photo: Joseph Scherschel/LIFE) | Rebel fire bombing, Prado Park Havana 9 April 1958 (photo: Bettmann/CORBIS) |

based on Manuel Márquez-Sterling's Cuba 1952-1959 and

Cuba 1952-1959 Interactive Timeline

Cuba 1952-1959 Interactive Timeline

Labels:

Cuba 1958,

Cuba history,

Timeline Event

Monday, October 19, 2009

1958: Congress declares State of Emergency

Cuba History Timeline Events

March 31, 1958

In response to the escalating terrorism and the M-26-7 “Total War” initiative, the Batista government invoked constitutional provisions that gave congress the authority to declare a national state of emergency giving the executive exceptional temporary powers. The congress, at the request of the Council of Ministers, passed special legislation declaring a “State of National Emergency” granting Batista extraordinary powers for a forty-five day period.

The law was publicly announced in Cuba’s Gaceta Oficial de la República on April 1, 1958. This act gave the President broad emergency powers including including the right to impose martial law, govern by decree, and use troops against strikers. These provisions effectively remained in force until the end of the Batista regime, renewed by passing extensions. These were enacted on 17 May (Special Act #2, State of National Emergency), 23 July (Decree 2418), 7 September (Decree 3023), and 22 October (Decree 3548), all published in Gaceta Oficial.

Contemporaneous coverage in the NY Times reflected the increasing and ever bolder attacks of the rebels as they prepared for their impending total victory on April 9 when they unleashed their “ultimate weapon”- the General Strike that would paralyze the island with military and terrorist support from the revolutionaries. This coverage acknowledged that the union leadership (CTC) had decided not to support the strike. The NY Times coverage in reporting the increased intensity and scope of rebel attacks, prepared its readers for the impending triumph of Castro in April:

Cuba is waiting anxiously for the “total war” that Fidel Castro, rebel leader, has threatened to start in Oriente Province today against the Government of President Fulgencio Batista.

Military action by the rebels is scheduled to be accompanied by a Cuba revolutionary strike as a supreme effort to overthrow the Batista regime.

March 31, 1958

In response to the escalating terrorism and the M-26-7 “Total War” initiative, the Batista government invoked constitutional provisions that gave congress the authority to declare a national state of emergency giving the executive exceptional temporary powers. The congress, at the request of the Council of Ministers, passed special legislation declaring a “State of National Emergency” granting Batista extraordinary powers for a forty-five day period.

The law was publicly announced in Cuba’s Gaceta Oficial de la República on April 1, 1958. This act gave the President broad emergency powers including including the right to impose martial law, govern by decree, and use troops against strikers. These provisions effectively remained in force until the end of the Batista regime, renewed by passing extensions. These were enacted on 17 May (Special Act #2, State of National Emergency), 23 July (Decree 2418), 7 September (Decree 3023), and 22 October (Decree 3548), all published in Gaceta Oficial.

Contemporaneous coverage in the NY Times reflected the increasing and ever bolder attacks of the rebels as they prepared for their impending total victory on April 9 when they unleashed their “ultimate weapon”- the General Strike that would paralyze the island with military and terrorist support from the revolutionaries. This coverage acknowledged that the union leadership (CTC) had decided not to support the strike. The NY Times coverage in reporting the increased intensity and scope of rebel attacks, prepared its readers for the impending triumph of Castro in April:

Cuba is waiting anxiously for the “total war” that Fidel Castro, rebel leader, has threatened to start in Oriente Province today against the Government of President Fulgencio Batista.

Military action by the rebels is scheduled to be accompanied by a Cuba revolutionary strike as a supreme effort to overthrow the Batista regime.

based on Manuel Márquez-Sterling's Cuba 1952-1959 and

Cuba 1952-1959 Interactive Timeline

Cuba 1952-1959 Interactive Timeline

Labels:

Cuba 1958,

Cuba history,

Timeline Event

Tuesday, October 13, 2009

1958: Elections Postponed to November

Cuba History Timeline Events

March 26, 1958

Revolutionary violence against presidential candidates and their supporters achieved its aim, scuttling the June elections. Two March proceedings resulted in a five month postponement.

The Supreme Electoral Court granted the request for postponement sought by all political parties in a joint action citing the violence preventing orderly campaigning or voting. In a parallel effort, at the request of the Cabinet, the Congress passed a law on March 26 adjusting the electoral code, statutorily establishing the new date for elections as November 3, 1958.

A confidential telegram to the US State Department from Ambassador Smith about the situation summarizes a conversation he had with the Prime Minister, Gonzalo Güell y Morales de los Ríos. This reported that the Batista government had honored opposition candidates’ requests to postpone the election. This telegram also mentions that Güell believed that constitutional guarantees had been restored too soon and were exploited by the revolutionaries to increase violence to a level that jeopardized preservation of law and order. Amb. Smith noted:

Guell continued, "It is true and unfortunate that police at times are over-zealous—I am against any sort of violence—I am against dictatorship—I believe in democracy. Batista would like a democratic policy. If Castro succeeds, Cuba will have a real dictatorship. With Castro's Communistic projected program, situation in Cuba will be worse than in any other Latin American country—and that includes Guatemala".

Guell continued, "No matter who is elected in the coming elections, Castro will continue to fight. We must weaken Castro to make him play ball. Castro will not accept military junta or any government that is not 'stained' for him. All you have to do is read Castro's platform (22 points) and his letter to junta in Florida and then draw your own conclusions. Batista wants to leave power on February 24, 1959, and leave a government headed by a president elected by the people, whether the candidate be from the government party or the opposition party. Batista wants to guarantee a normal and democratic development of the country."

March 26, 1958

Revolutionary violence against presidential candidates and their supporters achieved its aim, scuttling the June elections. Two March proceedings resulted in a five month postponement.

The Supreme Electoral Court granted the request for postponement sought by all political parties in a joint action citing the violence preventing orderly campaigning or voting. In a parallel effort, at the request of the Cabinet, the Congress passed a law on March 26 adjusting the electoral code, statutorily establishing the new date for elections as November 3, 1958.

A confidential telegram to the US State Department from Ambassador Smith about the situation summarizes a conversation he had with the Prime Minister, Gonzalo Güell y Morales de los Ríos. This reported that the Batista government had honored opposition candidates’ requests to postpone the election. This telegram also mentions that Güell believed that constitutional guarantees had been restored too soon and were exploited by the revolutionaries to increase violence to a level that jeopardized preservation of law and order. Amb. Smith noted:

Guell continued, "It is true and unfortunate that police at times are over-zealous—I am against any sort of violence—I am against dictatorship—I believe in democracy. Batista would like a democratic policy. If Castro succeeds, Cuba will have a real dictatorship. With Castro's Communistic projected program, situation in Cuba will be worse than in any other Latin American country—and that includes Guatemala".

Guell continued, "No matter who is elected in the coming elections, Castro will continue to fight. We must weaken Castro to make him play ball. Castro will not accept military junta or any government that is not 'stained' for him. All you have to do is read Castro's platform (22 points) and his letter to junta in Florida and then draw your own conclusions. Batista wants to leave power on February 24, 1959, and leave a government headed by a president elected by the people, whether the candidate be from the government party or the opposition party. Batista wants to guarantee a normal and democratic development of the country."

|  |

| US Ambassador to Cuba Earl ET Smith, Havana 1958 (photo: Lester Cole/CORBIS) | Prime Minister Gonzalo Güell (R) and Batista, 1958 (photo: Joseph Scherschel/LIFE) |

based on Manuel Márquez-Sterling's Cuba 1952-1959 and

Cuba 1952-1959 Interactive Timeline

Cuba 1952-1959 Interactive Timeline

Labels:

Cuba 1958,

Cuba 1958 elections,

Cuba history,

Timeline Event

Monday, October 12, 2009

1958: Revolutionary Ides of March

Cuba History Timeline Events

March 15, 1958

Mid-March was a time of jubilation for the revolutionaries, and a bleak month for Batista—and the electoralist-constitutionalist opposition.

Castro's strategy was paying off. His terror campaigns backed Batista into a corner where he increasingly had to choose between restricting civil rights (particularly detention and interrogation of terror suspects) or letting the country slide into chaos. And simultaneously, regardless of the course Batista chose, the same climate of terror would preclude the possibility of conducting political campaigns or holding the scheduled elections. And the long in planning General Strike threatened to paralyze the island.

Confident that his victory in April was inevitable, Castro tightened cooperation with Cuba’s Communist Party (PSP) even as he rebuffed and distanced himself from the Church and its peace initiative. He engaged the Cuban Communist Party in his grand strike plan, and they pledged their support in March.

Multiple Castro initiatives converged this month to severely impair Batista’s capacity to maintain the climate conducive to free elections negotiated with the electoralists as their sine qua non conditions for participating in elections. These subversive initiatives included:

Tactics against political rivals included intimidation of opponents and aggressive efforts to discredit them by painting those who sought elections as Batistianos (Batista supporters), and even claiming that they were receiving payoffs from the government.

The March successes of Castro’s tactics brought joy to the revolutionaries and sorrow to the constitutionalists. Carlos Márquez-Sterling response was “This is what we wanted to avoid at all costs. Our work has just become much more difficult.”

For the electoralist-constitutionalist opposition to Batista, the already enormous challenge of crafting and achieving a political solution threatened to become insurmountable as the national political climate was poisoned to the point that violence threatened to become the only way to settle differences. And the damage done to Cuba’s democratic institutions left them increasingly vulnerable to being overrun by a totalitarian tyrant.

March 15, 1958

Mid-March was a time of jubilation for the revolutionaries, and a bleak month for Batista—and the electoralist-constitutionalist opposition.

Castro's strategy was paying off. His terror campaigns backed Batista into a corner where he increasingly had to choose between restricting civil rights (particularly detention and interrogation of terror suspects) or letting the country slide into chaos. And simultaneously, regardless of the course Batista chose, the same climate of terror would preclude the possibility of conducting political campaigns or holding the scheduled elections. And the long in planning General Strike threatened to paralyze the island.

Confident that his victory in April was inevitable, Castro tightened cooperation with Cuba’s Communist Party (PSP) even as he rebuffed and distanced himself from the Church and its peace initiative. He engaged the Cuban Communist Party in his grand strike plan, and they pledged their support in March.

Multiple Castro initiatives converged this month to severely impair Batista’s capacity to maintain the climate conducive to free elections negotiated with the electoralists as their sine qua non conditions for participating in elections. These subversive initiatives included:

- Greatly increased terrorism, aiming at destroying the economy (Sugar harvest focus)

- Opening Sierra Cristal Front which would focus on new forms of terror, and terror against US citizens and interests

- Enrollment of members of the judiciary in publicly opposing the government

- Enrollment of the “non-partisan” Civic Associations Organization in calling for Batista’s resignation and supporting M-26-7 proposals

- Success in lobbying US (through press, congressional, and State Department sympathizers) to impose arms embargo on Cuban government, progressively withdrawing support from Batista

- Impeding the scheduled June elections

Tactics against political rivals included intimidation of opponents and aggressive efforts to discredit them by painting those who sought elections as Batistianos (Batista supporters), and even claiming that they were receiving payoffs from the government.

The March successes of Castro’s tactics brought joy to the revolutionaries and sorrow to the constitutionalists. Carlos Márquez-Sterling response was “This is what we wanted to avoid at all costs. Our work has just become much more difficult.”

For the electoralist-constitutionalist opposition to Batista, the already enormous challenge of crafting and achieving a political solution threatened to become insurmountable as the national political climate was poisoned to the point that violence threatened to become the only way to settle differences. And the damage done to Cuba’s democratic institutions left them increasingly vulnerable to being overrun by a totalitarian tyrant.

based on Manuel Márquez-Sterling's Cuba 1952-1959 and

Cuba 1952-1959 Interactive Timeline

Cuba 1952-1959 Interactive Timeline

Labels:

Cuba 1958,

Cuba 1958 elections,

Cuba history,

Timeline Event

Tuesday, October 6, 2009

1958: Civic Associations Organization letter

Cuba History Timeline Events

March 14, 1958

Concerned with the worsening political situation, US Ambassador Smith met with Raúl Velasco Guzmán, chairman of Cuba’s Civic Associations Organization (Conjunto de Instituciones Cívicas de Cuba). He urged Velasco to recommend that his members publicly support the June elections, and tell them that Batista had agreed to having US, UN, or OAS observers supervise the elections if the civic associations requested it.

With apparent reluctance Velasco said he would call for a meeting of his association to discuss Amb. Smith's request. He never did. Two days later, Velasco sent Smith an open letter listing more than 40 civic associations as signatories (but without signatures). This public letter from the Civic Associations Organization which implicitly rejected Smith’s call did not even mention Batista’s offer for election monitoring by international observers. The public letter from the Civic Associations Organization called on Batista to resign and implicitly supported Castro’s demands.

Smith doubted Velasco's good faith and his claimed "non-partisanship". The revelations of history confirm his doubts. It was later revealed that Velasco was a loyal and trusted closeted Castro supporter, and M-26-7's first choice to be Provisional President on the fall of Batista. Unknown to Smith, the "non-partisan" Velasco had been offered the revolutionary government Provisional Presidency a few months before, prior to its being offered to Urrutia.

March 14, 1958

Concerned with the worsening political situation, US Ambassador Smith met with Raúl Velasco Guzmán, chairman of Cuba’s Civic Associations Organization (Conjunto de Instituciones Cívicas de Cuba). He urged Velasco to recommend that his members publicly support the June elections, and tell them that Batista had agreed to having US, UN, or OAS observers supervise the elections if the civic associations requested it.

With apparent reluctance Velasco said he would call for a meeting of his association to discuss Amb. Smith's request. He never did. Two days later, Velasco sent Smith an open letter listing more than 40 civic associations as signatories (but without signatures). This public letter from the Civic Associations Organization which implicitly rejected Smith’s call did not even mention Batista’s offer for election monitoring by international observers. The public letter from the Civic Associations Organization called on Batista to resign and implicitly supported Castro’s demands.

Smith doubted Velasco's good faith and his claimed "non-partisanship". The revelations of history confirm his doubts. It was later revealed that Velasco was a loyal and trusted closeted Castro supporter, and M-26-7's first choice to be Provisional President on the fall of Batista. Unknown to Smith, the "non-partisan" Velasco had been offered the revolutionary government Provisional Presidency a few months before, prior to its being offered to Urrutia.

based on Manuel Márquez-Sterling's Cuba 1952-1959 and

Cuba 1952-1959 Interactive Timeline

Cuba 1952-1959 Interactive Timeline

Labels:

Cuba 1958,

Cuba 1958 elections,

Cuba history,

Timeline Event

Monday, October 5, 2009

1958: US Support Ends; Cuba Embargo imposed

Cuba History Timeline Events

March 14, 1958

US Ambassador Smith noted a critical turning point, writing in his book The Fourth Floor:

“March 12, 1958 is an important date in Cuban history. After that date it was no longer possible to engender any support in the [US] State Department for the Batista government. It was on March 12 that Batista found it necessary to renew the suspension of constitutional guarantees and to reimpose censorship of the press.”

The ambassador summarized how this turn of events shifted power in the US State Department:

“For months I had used every means of persuasion to convince Batista to restore constitutional guarantees in the island. Overruling the advice of his confidants he complied and did so on January 25. The Department, believing this to be a big step in the right direction, assumed a waiting attitude. As I mentioned before they agreed to renew delivery instructions for twenty armored cars, which had been on order for some time.

Now, after approximately seven weeks, the strong man was forced to clamp down again because of the stepped-up activities of the terrorists. The waiting attitude ended. The Rightist-dictator-haters and the pro-Castro elements, whose estimate of the situation was that Batista could only control through strong-arm methods, were back in charge.”

The ambassador’s assessment of support having ended for the government of Cuba was publicly visible in the imposition on March 14 of an arms embargo, halting all armament and other military shipments to Batista’s government, even enforcing the embargo by intercepting ships enroute to turn them back to US ports. The embargo strictures even extended to forbidding the use of earlier supplied US armaments to suppress domestic rebellion.

The Eisenhower administration cited its reasons for the embargo as not wanting US-supplied weapons to be used in a civil war. The persistent lobbying of Castro and his revolutionary allies for a US embargo achieved their intended result. While the State Department enforced the embargo on Batista, with American tacit consent Castro continued to receive armaments and military supplies.

At this time the ambassador came to appreciate more fully how correct Assistant Secretary of State Robert C. Hill was in confiding when he accepted the post that Smith would be presiding over Batista’s demise since the US had already decided Batista had to go.

March 14, 1958

US Ambassador Smith noted a critical turning point, writing in his book The Fourth Floor:

“March 12, 1958 is an important date in Cuban history. After that date it was no longer possible to engender any support in the [US] State Department for the Batista government. It was on March 12 that Batista found it necessary to renew the suspension of constitutional guarantees and to reimpose censorship of the press.”

The ambassador summarized how this turn of events shifted power in the US State Department:

“For months I had used every means of persuasion to convince Batista to restore constitutional guarantees in the island. Overruling the advice of his confidants he complied and did so on January 25. The Department, believing this to be a big step in the right direction, assumed a waiting attitude. As I mentioned before they agreed to renew delivery instructions for twenty armored cars, which had been on order for some time.

Now, after approximately seven weeks, the strong man was forced to clamp down again because of the stepped-up activities of the terrorists. The waiting attitude ended. The Rightist-dictator-haters and the pro-Castro elements, whose estimate of the situation was that Batista could only control through strong-arm methods, were back in charge.”

The ambassador’s assessment of support having ended for the government of Cuba was publicly visible in the imposition on March 14 of an arms embargo, halting all armament and other military shipments to Batista’s government, even enforcing the embargo by intercepting ships enroute to turn them back to US ports. The embargo strictures even extended to forbidding the use of earlier supplied US armaments to suppress domestic rebellion.

The Eisenhower administration cited its reasons for the embargo as not wanting US-supplied weapons to be used in a civil war. The persistent lobbying of Castro and his revolutionary allies for a US embargo achieved their intended result. While the State Department enforced the embargo on Batista, with American tacit consent Castro continued to receive armaments and military supplies.

At this time the ambassador came to appreciate more fully how correct Assistant Secretary of State Robert C. Hill was in confiding when he accepted the post that Smith would be presiding over Batista’s demise since the US had already decided Batista had to go.

based on Manuel Márquez-Sterling's Cuba 1952-1959 and

Cuba 1952-1959 Interactive Timeline

Cuba 1952-1959 Interactive Timeline

Labels:

Cuba 1958,

Cuba history,

Timeline Event

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

Mobile subscription

Mobile subscription