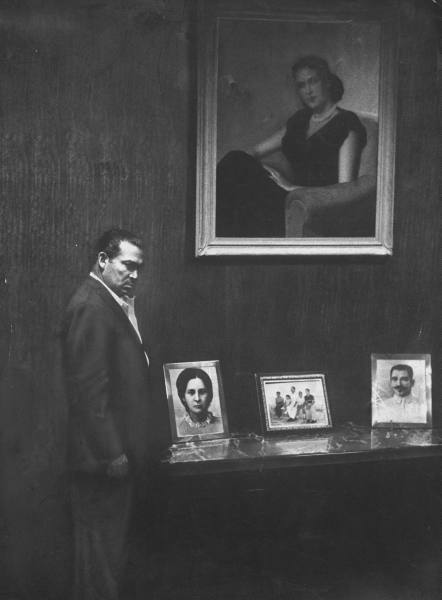

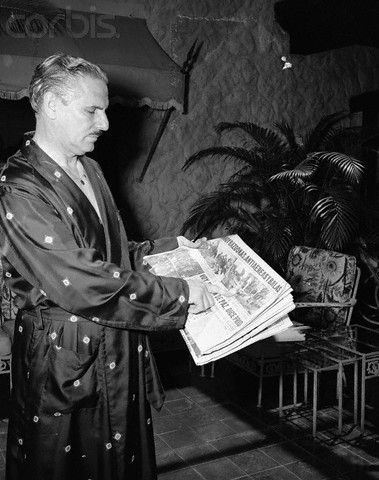

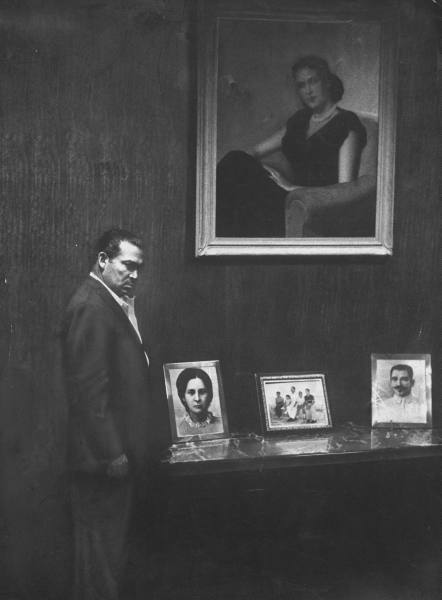

Cuba Photo Reflections  Fulgencio Batista in his office at the Presidential Palace,

Fulgencio Batista in his office at the Presidential Palace,

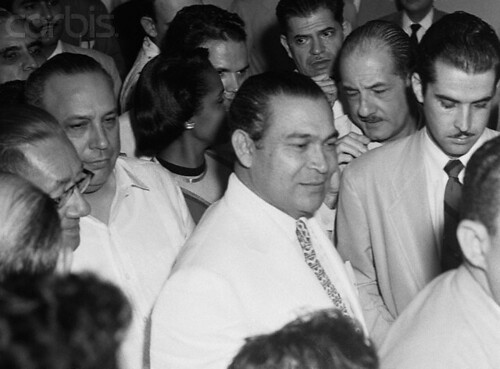

Havana, Cuba March 1957 . LIFE photo by Grey VilletThe man in the picture, Fulgencio Batista, is usually known to American readers as a caricature: “the US-backed dictator” overthrown by Castro, an “oppressive brutal tyrant” who could be removed only by violent revolution. But it is an open secret among competent historians that such simplistic characterizations of the man are a grotesque distortion, serving primarily as a cornerstone in furtherance of the Castro Revolutionary Myth. These cartoonish portrayals were originally penned by revolutionary student radicals as part of an amoral agenda that embraced deception and terrorism as political tools. They have been repeated incessantly and uncritically by the press (even within 50s Cuba as they accused him of censorship), and for over 50 years have been amplified by the Castro regime. The reality of Batista’s role in Cuban history is much more complicated than that.

If Cuban history has a tragic figure in the classic sense, it is without doubt Fulgencio Batista. He almost seems a Shakespearean character, perhaps one reminiscent of Coriolanus. This picture, taken in March 1957 by Grey Villet, speaks thousands of words. It captures a man deep in thought reflecting upon his past. A past summoned by pictures of his forebears on the table and his wife’s portrait on the wall. A past considered in a present just after revolutionary student radicals had made a daring attempt on his life in the very place where this picture was taken. Since that building (the Presidential Palace) also served as the presidential residence, the armed assault and ensuing gun battle had imperiled the lives of his wife and children. Among the casualties of the attack were an American tourist two blocks away killed by a stray bullet. Had Batista not broken with his normal schedule to check in on his sick son upstairs, the assassins would have found and killed him at his desk that afternoon.

There are thousands of pictures of Batista. None, however, shows so harsh a facial expression as this one. His severe expression betrays turmoil deep within his soul

(click here for detail). Even a casual observer cannot help but wonder what current deep in his stream of consciousness was powerful enough to disturb for an instant the disciplined face of a skillful politician practiced at being pleasant and even charming. Unquestionably the camera captured an unguarded moment allowing a fleeting glimpse into Batista’s thoughts. Thoughts that it will take future historians much reflection and many volumes to rediscover.

What do you read in that powerful expression? Dejection, futility, anger, despair, arrogance, rejection, defeat? or anguish for a momentous decision to make concerning the future of his country? Perhaps a brief account of Batista’s public life will help you deliberate.

Batista entered this world in 1901, a year before Cuban independence. His father was a veteran of the revolutionary war against Spain. Turn of the century Cuba was a poor country, its primitive economy decimated by the War of Independence. Its first thirty years would be economically trying and politically turbulent. Political changes (in which Batista figured prominently) beginning in 1933 would bring about an extraordinary national success story: in a little over 50 years after independence Cuba would overtake most of its regional neighbors and its colonial master Spain in the health, wealth, education and standard of living enjoyed by its citizens.

Batista was born in the town of Banes, Oriente province, to a poor rural family, some say of mixed racial background. His childhood home was a dirt floor

bohío, a primitive rustic dwelling, Cuba’s equivalent of a log cabin. He admired Abraham Lincoln and like him was an avid reader, almost fanatical about self-improvement, enrolling in night school and correspondence courses while working days as a cane cutter. In 1921, after obtaining a teaching degree he joined the Cuban army. He entered the pages of history in 1933 when he was involved in overthrowing Cuba’s first dictator, Gerardo Machado. Soon thereafter he rose to become the leader of that army, and a hero to its junior officers. While the younger officers and non-commissioned officers worshipped him, the senior officers despised him.

In the 1930s many of Cuba’s senior Army officers were 1895 War of Independence veterans, who along with other high ranking officers (mostly graduates of military colleges) formed a closed hierarchy that regarded the Army’s upper ranks as an entitlement reserved for their families. In many ways they were 19th century men unable and unwilling to adapt to the new ways and ideas of the 20th century, especially the idea of judging men by individual merits and achievements rather than lineage. During the chaotic days of 1933-34 hundreds of these officers holed up in the

Hotel Nacional, pitting senior officers against the non-commissioned officers and younger officers who supported Batista. After a siege of several weeks, they surrendered and shortly thereafter many of these senior officers retired, henceforth hating Batista for the "democratization" of Cuba’s armed forces. Batista gained in stature by his handling of this and subsequent insurrectional acts, successfully restoring civil order and governmental stability after Machado was overthrown.

By 1934 Batista was a force to be reckoned with, from his military headquarters exercising the powers of a maker and breaker of Presidents. During Cuba’s chaotic 1930s Batista had restored order by leading a coup that brought down a tyrannical dictator, but instead of becoming another Latin American dictator, as many encouraged him to do, he chose the high road. Following in the footsteps of Nicaragua’s Somoza, he could have become President Roosevelt’s new own “son of a bitch.” But Batista chose to follow a different course, recognizing there were strong civil society and political forces to contend with, he embraced the political compromise of 1939 which culminated in the restoration of full democracy in Cuba and in the farsighted Constitution of 1940. He was then elected president. After serving his full term he retired to Florida in 1944, honoring Constitutional term limits and the electoral results that defeated his favored successor.

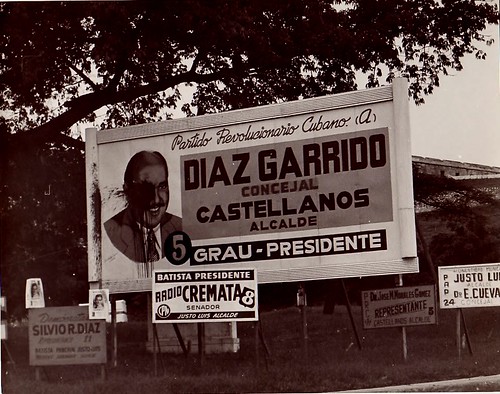

He had established the kind of legacy that earns leaders the gratitude of a people served well, and in time is expressed by naming monuments and streets to memorialize them. However, Batista foreclosed such honors and eclipsed his previous glory by overthrowing the constitutionally elected President Carlos Prío in 1952. Though he was again the master of Cuba, the 1952 coup overshadowed his earlier patriotic service. He had been one of the founding fathers of the new republic in 1940, but now like a flawed hero of ancient myths he succumbed to, and would ultimately be brought down by, his tragic flaw—perhaps a raw ambition for power.

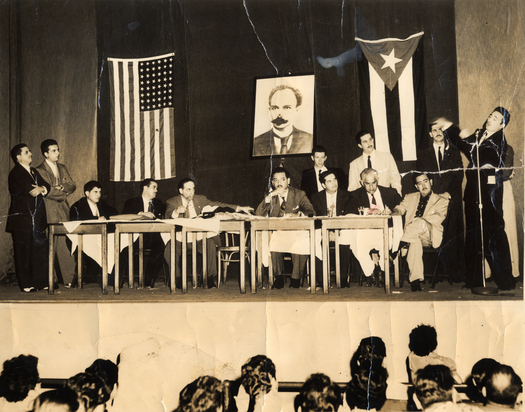

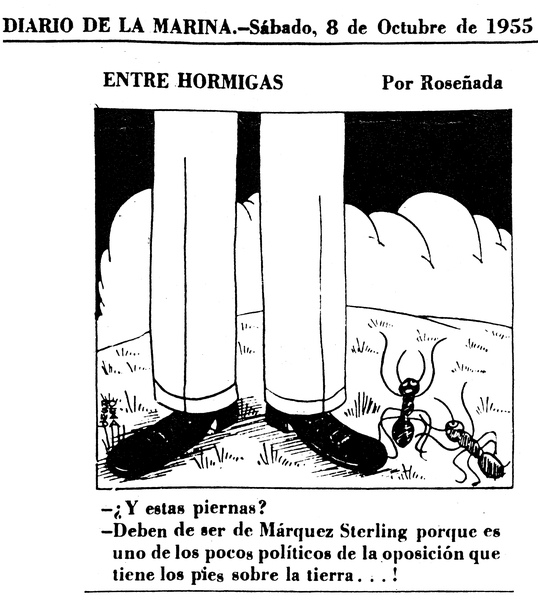

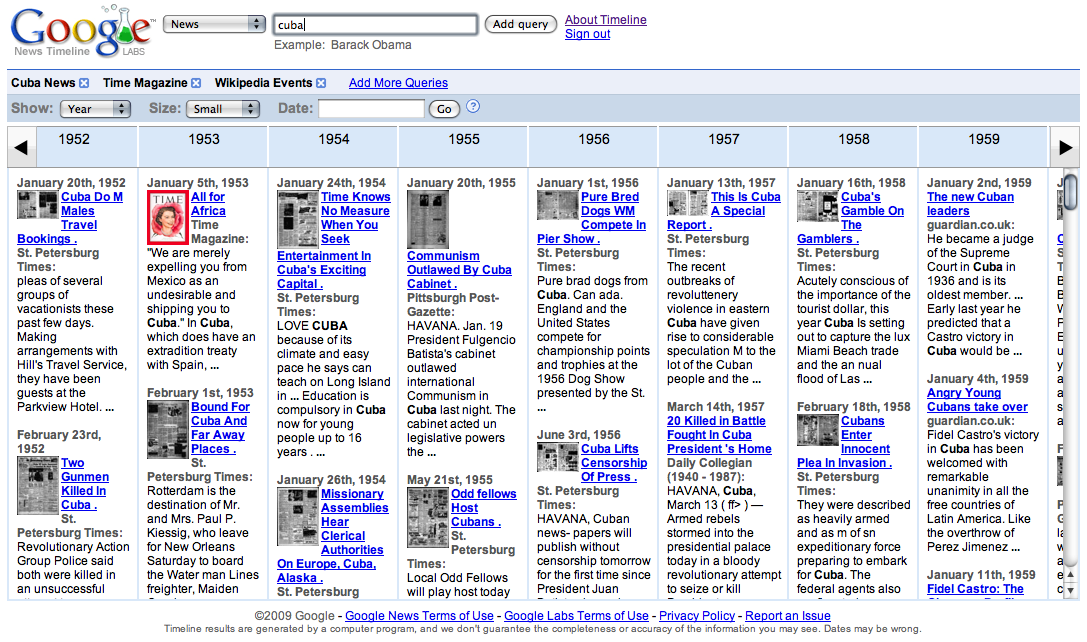

Opposition to Batista’s regime in the fifties soon split into two wings: the Revolutionaries (of which Castro’s movement was a part) and the Electoralists-Constitutionalists. The Revolutionaries gave him no quarter in their efforts to overthrow him by violent means, come what may. The Electoralists-Constitutionalists recognized Batista's ability and willingness to negotiate an end to his regime, and endeavored to engage him in order to end his rule through free and fair elections that would safeguard Cuba’s democratic institutions and quick return to constitutional rule, avoiding a revolutionary holocaust. Surmounting extraordinary obstacles, Batista and his major opponents agreed to hold elections in November of 1958.

The greatest irony in Batista’s political career is that the 1958 elections—in which he was not a candidate—cast him as the arbiter of Cuba’s destiny. The disjunctive at that time was clear to everyone. Either, as the electoralist-constitutionalist opposition anticipated, Batista held honest elections and saved Cuba from Castro’s revolution, or as Castro hoped, he rigged them and handed Cuba over to the totalitarian hordes of Fidel Castro and the Communists. Batista still had a chance to secure a milder judgment from history for his legacy. History, as it is well known, has recorded that he inexplicably chose the second alternative, thereby relinquishing his former place of honor in Cuban history. By rigging the 1958 elections Batista denied the Cuban people an alternative to the horrors of Castro's brutal tyranny. His puzzling choice remains the greatest paradox of this paradoxical man, who entitled his memoirs

Paradoxes (

Paradojas).

The end of Batista’s dictatorship was precipitated by the US ambassador telling him in December of 1958 that its dwindling support was about to end and that he should resign. This put Batista in the situation faced in 1933 by Machado, the dictator whose overthrow launched his political life. As in 1933, the US State Department simultaneously conveyed increasing support to Castro’s forces, communicating their intentions to quickly recognize a Castro government if it seized power.

Batista had admired and supported the US, a country that supported his generation in overthrowing the dictatorship of Machado, and supported his father’s generation in gaining independence from Spain. But in 1959 he was denied admission to the US, forcing him to take refuge in Spain, the country he and his father had been at war with as allies of the US. He spent the remaining years of his life in Spain, where he died scorned and ostracized in 1973.

In reflecting upon Batista’s complex role in Cuban history, it is imperative to consider that most of the accounts published about him are demonization screeds produced to serve as the cornerstone of the Castro Revolutionary Myth. They were ably crafted to serve this purpose in three ways. First, they obscure that vast majority of the opposition to Batista was not the violent revolutionaries but the electoralists seeking a political solution—which Batista was willing and able to negotiate. Castro and the revolutionaries early showed their anti-democratic intentions by unleashing savage attacks rhetorical and physical against all engaged in seeking political solutions that would end the Batista regime while preserving democracy and returning to constitutional rule. These concerted attacks by Castro and the revolutionaries effectively subverted and sabotaged electoralist initiatives, and were the main reason for their failure.

Second, by demonizing Batista into a brutal oppressor that had to be violently overthrown it becomes justifiable—even admirable—to have used guerrilla insurgency and terrorism to defeat him—and this transmutes Castro’s ragtag gang of thugs, criminals, misfits, and misguided young idealists into heroic figures. This also foists the illusion that there were only two actors in 50s Cuba: Batista and Castro. Third, they obscure the reality that under Batista’s regime Cubans were healthier, wealthier and freer than they have ever been under Castro’s tyranny.

It is fitting that Batista be remembered as a dark figure, the man who dealt a fatal blow to the Old Republic of Cuba directly causing its collapse. But this doesn’t require denying the truth that this was a complex man who earlier accomplished much that was good for Cuba and Cubans, or the incontrovertible truth that his dictatorship was a far lesser evil than Castro’s with respect to Cuba’s economy or the standard of living and civil liberties of its citizens.

Mobile subscription

Mobile subscription